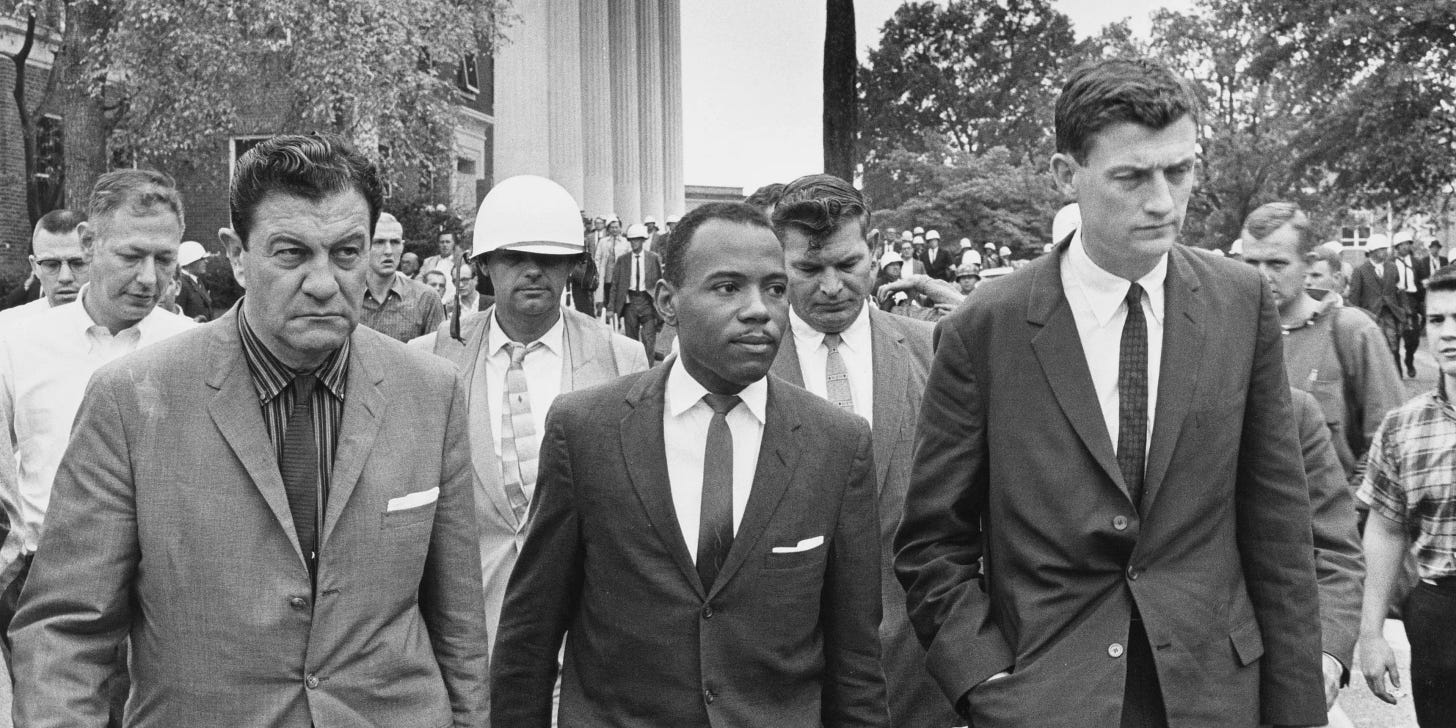

James Meredith, the Kennedy brothers, & the '62 integration

An addendum to Heather Cox Richardson's recent post

Last week, historian

wrote about November, 22, 1963, the day President John F. Kennedy was shot. The background to his assassination was also explained — a background that poignantly involves the events surrounding my father-in-law’s integration into the University of Mississippi.Just over a year prior to the events, the Kennedy brothers turned on the party’s southern wing and backed the decision of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. This, in effect, gave James Meredith the right to officially enroll at Ole Miss.

Richardson goes on to say the following:

When the Department of Justice ordered officials at Ole Miss to register Meredith, Mississippi governor Ross Barnett physically barred Meredith from entering the building and vowed to defend segregation and states’ rights.

So the Department of Justice detailed dozens of U.S. marshals to escort Meredith to the registrar and put more than 500 law enforcement officers on the campus. White supremacists rushed to meet them there and became increasingly violent. That night, Barnett told a radio audience: “We will never surrender!” The rioters destroyed property and, under cover of the darkness, fired at reporters and the federal marshals. They killed two men and wounded many others.

The riot ended when the president sent 20,000 troops to the campus. On October 1, Meredith became the first Black American to enroll at the University of Mississippi.

When the Kennedy administration took a stand for Black rights, it “stoked such anger in the southern right wing that Kennedy felt obliged to travel to Dallas to try to mend some fences in the state Democratic Party” — and ultimately led to Kennedy’s assassination.

Do read the post in full, if you haven’t already. I admire Richardson’s work and am grateful to continue to learn from her!

When multiple friends and readers sent me last week’s post, I read it in full, several times in fact. I do not claim to be an historian, although I’ve been known to nerd out on history, given the chance.

However, I have studied in depth the two events my father-in-law is most known for in American history: his integration into Ole Miss in ‘62 and the Meredith March Against Fear in ‘66. My first book, The Color of Life, extensively covers both of these events, as well as my personal journey into issues of race and privilege.1

Although Richardson did not explicitly state that his integration into Ole Miss happened solely because of the Kennedy brothers, I think it’s important to note that their actions were merely icing on the cake — very yummy, gooey, important actions, no less, but the final result of years of intentional work to upset deep-seated systems of white supremacy that continued to grip institutional education in his home state.

To my father-in-law, his integration was something that began at birth: J.H. (as he was known as a child) “believed he’d been born to pass on the legacy of his great-grandfather, the last leader of the Choctaw Nation.”2 By the time he returned to Mississippi after serving nine years in the U.S. Air Force, he returned with the intention of getting a degree from the most segregated university in the state.

It was then that a three-year journey began:

In a strategy designed to hold the Kennedy administration accountable to the civil rights platform President Kennedy ran on during his election, James Meredith reached out to Ole Miss the day after Kennedy’s inauguration. The University of Mississippi registrar, Robert Ellis, enthusiastically acknowledged his ample qualifications as a transfer student upon receipt of his first letter:3 “We are very pleased to know of your interest in becoming a member of our student body,” Ellis stated. With that response, the real work began.4

As I mentioned to a friend, this was no solo effort. After the initial response, he met with local activist Medgar Evars and penned a letter to Thurgood Marshall, director of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. He began to gird up a team of folks, including, eventually, the Kennedy brothers, who worked with him to advance the mission.

Eventually, the NAACP provided assistance through prominent civil rights attorney Constance Baker Motley. With Motley at his side, the case bounced through various courts for nearly eighteen months until it reached the aforementioned Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. When the District Court finally entered an injunction forcing the University to register my father-in-law, the state of Mississippi continued to put up a fight.

The state would continue to do everything they could to uphold their southern values, including the value of segregation, which Ross Barnett had run on. They would not stand for another integration (as had been the case with the Little Rock Nine) — and neither would their supporters. “As the integration drew near, various white supremacist groups, like the United Klans of America, began rallying troops from as far as as California and as close as the bordering states — Louisiana, Alabama, and Georgia.”5

By this point, the Kennedy brothers were fully involved. After all, this was an instance of “the North versus the South, the United States government versus one of its own states, and the University of Mississippi was caught in the middle of it all.”6

By the time three hundred US marshals arrived to maintain peace and escort him to class the next morning, more than three hundred journalists had already arrived in Oxford and a growing mob of two thousand segregationists had already gathered to protest the event. By dusk, the marshals had already fired the first round of tear gas and the growing mob had begun to attack — and overwhelm — the wearying crew of marshals who hadn’t yet been allowed to fire their guns.

Soon, nearly fifteen thousand troops from the Mississippi National Guard and the US Army were called in as reinforcements, and an additional sixteen thousand arrived in northern Mississippi thereafter. Working together, they finished driving rioters off the campus by 2:15 in the morning and declared the campus secure four hours later.7

Is it any wonder the Democratic party’s southern wing continued to hold a grudge more than a year later, a grudge that ultimately resulted in the death of one of our country’s most popular Presidents?

For my father-in-law, though, this mission was not something that happened in a silo — nor was it something that the Kennedy brothers alone commandeered.

Instead, this was an event of calculation, patience, and intentionality that ultimately changed the world.

I can’t help but think: How might the rest of us might approach the events to which we have been called with equal parts calculation, patience, and intentionality? How might this change the world?

It’s a thought.

Yes, the book is still available! Order it from Bookshop or purchase an autographed copy through my website.

The Color of Life, 58.

He actually held credits from three different institutions (credits obtained from his time in the Air Force). When he moved back to Mississippi in the fall of 1960, he enrolled as an advanced junior at Jackson State University. Did he need to finish his education at Ole Miss? In theory, no. But in an effort to overturn the system? Absolutely.

The Color of Life, 60.

The Color of Life, 63.

The Color of Life, 63.

The Color of Life, 67.

What a proud legacy for your family.

Thank you for writing about your father-in-law and the history around his enrollment at the University of Mississippi. It’s great right now to have a reminder of how far we’ve come, especially considering everything that’s going on in politics currently. It’s so easy to feel discouraged, but it gives me hope for the future to be reminded about the progress that has been made in the past.